THE FAKEOUT

THE FAKEOUT

For a better understanding of liquidity please refer to the Order Flow and Liquidity Gap articles.

What is a Fakeout?

Fakeout is also known as False Breakout,

Shakeout, Sellers/Buyers/Bull/Bear Trap, Stop Run, Stop Hunt and

Liquidity Spike. It’s a search of liquidity followed by a change in

direction.

Why does it happen?

There are different scenarios and

situations of why it happens. However, the main reason behind it is to

create liquidity in an illiquid market - by big funds, to test a level’s

strength.

To elaborate more on that, a short example is required:

Let’s say price of a financial

instrument is rising to a value of significant history at 100

(resistance level) where the majority of traders will either buy a

breakout with stops below 100 or sell on rebound with stops above 100.

The price moves higher to 105 triggering on its way seller’s stops and

buyer’s orders, but price doesn’t get any higher and reverses back to

100 before dropping lower to 80.

So what has happened here?…Big funds

were planning to sell from 100, but, due to significance of the level,

so were the other market participants. So if the whole market is selling

at 100 then there are no buyers (lack of liquidity). If pro money sold

at 100 they would get a bad fill as price would quickly move away from

their entry. In order to get buyers for their sells, they must create

liquidity, by moving price a bit higher above 100, to induce buyers to

jump in as well as triggering seller’s stops which add to the buying

pressure. This will help fill their mass sell orders.

At the same time they’re able to test if

the level holds against the buying pressure. The presence of other

bullish big funds would’ve moved price up with momentum.

When pro money started selling, price

fell below the 100 triggering buyer’s stops and new sellers jumped in,

all adding to the selling momentum.

Where does it happen?

Around significant areas where stops are

placed, and breakout traders await to buy/sell, at unconsumed

Supply/Demand Zones, at Stacked Supply/Demand Zones, and at the end of a

Compression into Supply or Demand.

How to identify a Fakeout?

It can be identified in different ways,

such as candle close (or close of two combined candles) in relation to a

previous Swing High/Low, or a Support/Resistance, or a Key Level.

Now let’s go through some examples showing the different ways to identify a Fakeout:

At [1] price created a swing low then

moved up and returned back at [2] in a curvy shape breaking through the

swing low level but failed to close below and this is a Fakeout, next

price consolidated above the level retesting if level will hold then

moved up.

At [3] another swing low and a return at

[4], considering the space and time price took to return at [4] and the

acceptable curved shape, price created a Fakeout followed by a retest

and a second Fakeout before moving up.

At [5] a swing high and the return at

[6] wasn’t a good acceptable curvy shape, the Fakeout at [6] was to test

if level will hold and eventually it was broken.

You

can see two Fakeouts, one of a swing high level and another of a swing

low level. Both cases had an acceptable curvy return to test the swing

levels and without having to retest the Fakeouts price has changed

direction at both levels.

Before continuing the examples let’s first elaborate more about the curvy shape. The

main factors in a curvy shape to be taken into consideration are time

& space which price took to return to a swing point. The efficiency

of the shape itself could vary from a perfect arc to a triangle. Here

are some examples of a perfect curvy shape;

Now to continue with the Fakeout examples;

Price

created a supply zone at [1] and returned at [2] creating a lower high

before dropping and returning in a curvy shape for a 2nd visit

at [3] creating a Fakeout of preceded swing high from [2] and into the

supply followed by a drop in price. Considering the time frame; the move

down was effective until it flipped from an S/R flip level and an

ignored supply DP (Decision Point).

Price came back in a great curvy shape for a 2nd visit into demand at [2] creating a Fakeout of preceded swing low from [1] and a retest followed by a rally in price.

The same example zoomed out to the next higher time frame for a better visual of the DP (RBR) demand zone.

A demand zone at [1] and a 1st visit

at [3] and a Fakeout of a preceded swing low from [2] followed by a

change in direction. Notice the space and time between [2] & [3],

not so big but still the curvy shape from [2] to [3] is considerable.

The

same example zoomed out to the next higher time frame to show the

difference between time frames when spotting the curvy shape.

In the following two examples you’ll notice additional ways to identify a Fakeout:

At [1] a demand zone that was ignored

thus becoming supply, price dropped forming a support at [2] and an

ignored demand pocket followed by a drop and retest of broken support

becoming S/R flip and a Fakeout at [3] into ignored demand followed by

another drop in price.

At [4] a demand zone was created followed by another demand at [5] and a rally to [2] a 1st visit

to the ignored demand from [1] (now supply) then price compressed down

into the fresh demand at [5] creating a Fakeout at [6] followed by a

retest and a rally to [7] for a 2nd visit

into supply and a Fakeout of the preceded swing high from [2] followed

by a retest of the Fakeout and change in direction. Note that ignored

demand at [1] is totally consumed now and [7] is a fresh supply zone.

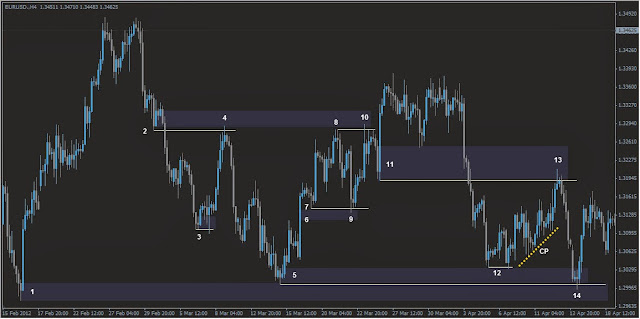

At [8] we have a swing high and at [9] a DP (RBR) demand followed by a rally to [10] and a 1st visit

into supply from [7], price moved down to [11] into demand from [9]

creating a Fakeout into support from [8] followed by a move up to [12]

back into supply for a 2nd visit and a Fakeout of the preceded swing high at [10] followed by a change in direction.

At [13] price returned back to the

demand from [4] digging deep into it and the spike that broke through

the zone with a close inside was a clear sign of consumption.

In this example we’ll speed up the process and point directly at the Fakeouts;

At [2] a support point and a DBD

(supply) followed by a drop in price to [3] creating a swing low and a

Fakeout (the curvy shape could be seen on a lower time frame). Price

returned to supply at [4] creating a Fakeout of the broken support point

from [2] followed by a change in direction.

At [9] a Fakeout of the support from [7] and into a LTF DP (RBR) from [6] followed by a change in direction.

At [10] a Fakeout of preceded swing high at [8] and into supply from [2] followed by a retracement.

At [12] a tiny Fakeout of preceded swing

low and into demand from [5] followed by a compression up. Note here

that recent price reaction to demand from [5] makes of it a stacked

demand above the lower demand from [1].

At [13] compression into ignored demand

from [11] turned supply and a Fakeout of resistance (LQ Spike) followed

by a change in direction.

At [14] another visit to stacked demand

zones and a spike into the lower demand zone as well as a Fakeout of the

swing low from [5] followed by a change in direction.

Proof of market manipulation from the Market Wizards Book:

Ref: Market Wizards - Paul Tudor interview;

That sounds like a general character-building lesson. What about specifics regarding trading?

"Tullis taught me about moving volume. When you are trading size, you have to get out when the market lets you out, not when you want to get out.

He taught me that if you want to move a large position, you don't wait until the market is in new high or low ground because very little volume may trade there if it is a turning point.

One thing I learned as a floor trader was that if, for example, the old high was at 56.80, there are probably going to be a lot of buy stops at 56.85. If the market is trading 70 aid, 75 offered, the whole trading ring has a vested interest in buying the market, touching off those stops, and liquidating into the stops—that is a very common ring practice. As an upstairs trader, I put that together with what Eli taught me. If I want to cover a position in that type of situation, I will liquidate half at 75, so that I won't have to worry about getting out of the entire position at the point where the stops are being hit. I will always liquidate half my position below new highs or lows and the remaining half beyond that point."

Ref: Market Wizards - Monroe Trout interview;

What else did you learn on the floor?

I learned about where people like to put stops.

Where do they like to put stops?

Right above the high and below the low of the previous day.

One tick above the high and one tick below the low?

Sometimes it might be a couple of ticks, but in that general area.

Basically, is it fair to say that markets often get drawn to these points? Is a concentration of stops at a certain area like waving a red flag in front of the floor brokers?

Right. That's the way a lot of locals make their money. They try to figure out where the stops are, which is perfectly fine as long as they don't do it in an illegal way.

Given that experience, now that you trade off the floor, do you avoid using stops?

I don't place very many actual stops. However, I use mental stops. We set beepers so that when we start losing money, a warning will go off, alerting us to begin liquidating the position.

What lesson should the average trader draw from knowing that locals will tend to move markets toward stop areas?

Traders should avoid putting stops in the obvious places. For example, rather than placing a stop 1 tick above yesterday's high, put it either 10 ticks below the high so you're out before all that action happens, or10 ticks above the high because maybe the stops won't bring the market up that far. If you're going to use stops, it's probably best not to put them at the typical spots. Nothing is going to be 100 percent fool proof, but that's a generally wise concept.

What else did you learn on the floor?

I learned about where people like to put stops.

Where do they like to put stops?

Right above the high and below the low of the previous day.

One tick above the high and one tick below the low?

Sometimes it might be a couple of ticks, but in that general area.

Basically, is it fair to say that markets often get drawn to these points? Is a concentration of stops at a certain area like waving a red flag in front of the floor brokers?

Right. That's the way a lot of locals make their money. They try to figure out where the stops are, which is perfectly fine as long as they don't do it in an illegal way.

Given that experience, now that you trade off the floor, do you avoid using stops?

I don't place very many actual stops. However, I use mental stops. We set beepers so that when we start losing money, a warning will go off, alerting us to begin liquidating the position.

What lesson should the average trader draw from knowing that locals will tend to move markets toward stop areas?

Traders should avoid putting stops in the obvious places. For example, rather than placing a stop 1 tick above yesterday's high, put it either 10 ticks below the high so you're out before all that action happens, or10 ticks above the high because maybe the stops won't bring the market up that far. If you're going to use stops, it's probably best not to put them at the typical spots. Nothing is going to be 100 percent fool proof, but that's a generally wise concept.

Ref: Market Wizards - Richard Dennis interview;

Can you give me an example of how the lack of real world experience would hurt the researcher?

As an example, assume I develop a mechanical system that often signals placement of stops at points where I know there will tend to be a lot of stops, in the real world, it is not too wise to have your stop where everyone else has their stop. Also, that system is going to have above-average skids. If you don't understand that and adjust the results accordingly, you are going to get a system that looks great on paper, but is going to do consistently poorer in the real world.

Can you give me an example of how the lack of real world experience would hurt the researcher?

As an example, assume I develop a mechanical system that often signals placement of stops at points where I know there will tend to be a lot of stops, in the real world, it is not too wise to have your stop where everyone else has their stop. Also, that system is going to have above-average skids. If you don't understand that and adjust the results accordingly, you are going to get a system that looks great on paper, but is going to do consistently poorer in the real world.

Ref: Market Wizards - Bruce Kovner interview;

Let's say you do buy a market on an upside breakout from a consolidation phase, and the price starts to move against you—that is, back into the range. How do you know when to get out? How do you tell the difference between a small pullback and a bad trade?

Whenever I enter a position, I have a predetermined stop. That is the only way I can sleep. I know where I'm getting out before I get in. The position size on a trade is determined by the stop, and the stop is determined on a technical basis. For example, if the market is in the midst of a trading range, it makes no sense to put your stop within that range, since you are likely to be taken out. I always place my stop beyond some technical barrier.

Don't you run into the problem that a lot of other people may be using the same stop point, and the market may be drawn to that stop level?

I never think about that, because the point about a technical barrier—and I've studied the technical aspects of the market for a long time—is that the market shouldn't go there if you are right. I try to avoid a point that floor traders can get at easily. Sometimes I may place my stop at an obvious point, if I believe that it is too far away or too difficult to reach easily.

To take an actual example, on a recent Friday afternoon, the bonds witnessed a high-velocity breakdown out of an extended trading range. As far as I could tell, this price move came as a complete surprise. I felt very comfortable selling the bonds on the premise that if I was right about the trade, the market should not make it back through a certain amount of a previous overhead consolidation. That was my stop. I slept easily in that position, because I knew that I would be out of the trade if that happened.

Talking about stops, I assume because of the size that you trade, your stops are always mental stops, or is that not necessarily true?

Let's put it this way: I've organized my life so that the stops get taken care of. They are never on the floor, but they are not mental.

Let's say you do buy a market on an upside breakout from a consolidation phase, and the price starts to move against you—that is, back into the range. How do you know when to get out? How do you tell the difference between a small pullback and a bad trade?

Whenever I enter a position, I have a predetermined stop. That is the only way I can sleep. I know where I'm getting out before I get in. The position size on a trade is determined by the stop, and the stop is determined on a technical basis. For example, if the market is in the midst of a trading range, it makes no sense to put your stop within that range, since you are likely to be taken out. I always place my stop beyond some technical barrier.

Don't you run into the problem that a lot of other people may be using the same stop point, and the market may be drawn to that stop level?

I never think about that, because the point about a technical barrier—and I've studied the technical aspects of the market for a long time—is that the market shouldn't go there if you are right. I try to avoid a point that floor traders can get at easily. Sometimes I may place my stop at an obvious point, if I believe that it is too far away or too difficult to reach easily.

To take an actual example, on a recent Friday afternoon, the bonds witnessed a high-velocity breakdown out of an extended trading range. As far as I could tell, this price move came as a complete surprise. I felt very comfortable selling the bonds on the premise that if I was right about the trade, the market should not make it back through a certain amount of a previous overhead consolidation. That was my stop. I slept easily in that position, because I knew that I would be out of the trade if that happened.

Talking about stops, I assume because of the size that you trade, your stops are always mental stops, or is that not necessarily true?

Let's put it this way: I've organized my life so that the stops get taken care of. They are never on the floor, but they are not mental.

By FX.Sniffer

Comments

Post a Comment